Heard not the Voice of a Bird, Boom Gallery 8th October -1st November

selected works , click the gallery link for complete list ^

As a school child in the seventies, on hot days, we were sometimes treated to a movie morning in the multi-purpose room. Before VHS, the room was set up like a theatre with a movie projector and reel to reels. We sat on the floor in rows and once we watched the Australian movie, Lost in the Bush (1973), based on a true account of three young children who became lost while gathering broom for their mother. At the time, being of similar age as the children in the movie, this tale of barely surviving in the Little Desert for nine days, had a huge impact on me. I remember the discussion afterward being very much a cautionary tale, in much the same way as Little Red Riding hood.

As I researched their real-life, eventual rescue (by Jardwadjali trackers), I found that the stories of the lost child and the “dangerous” bush have been woven into the way colonial history was told. Without a doubt, the landscape is treacherous for those who are unprepared. It is powerful and mysterious. While reading essays and articles about “the lost white child”, it’s evident that this kind of thing happened all the time.

“Heard not the voice of a bird” is a line from the quaint and poetic book The Australian Babes in the Wood, a true story (1866) written for children. Days into the trackers’ search, they think they hear the children calling out.

And a sudden start shook the tracker’s heart.

As the echo came – ‘Quite- quite right;’

For he thought he heard not the voice of a bird,

But the voice of children dear;

And he cooey’d shrill, but the voice was still,

And he saw not the wand’rers there.

The haunting soundtrack of Picnic at Hanging Rock was part of my introduction to how to feel about the Australian bush. The mysterious story of the fictional girls who wandered away from a picnic near Mount Macedon is the other part of my research.

Creating a visual language

Australia doesn’t really have much of a history of European style tapestry weaving in a historical way. Our indigenous plant life was not rendered in the form of tapestry, unlike the plants of Europe. Mille fleur, the intense patterning of flowers and foliage, that were used as a horror vacui in the backgrounds of tapestries like The Lady and the Unicorn suite are unknown here in Australia. One of my hopes with this work was to incorporate as much native foliage as I can, as a way to create a language that is specific to Australia. The female subjects also have strong Australian-ness , echoing rather than describing the stories mentioned above. The lace of the women’s clothing, to me, is the personification of the out-of-place person, who is unprepared to be in the Australian bush.

While researching, I travelled to Daylesford where three little boys disappeared in 1867. There is a kind of spontaneous shrine in the place where they were found. The children were found sheltering in a tree that was once there. On the way to this site I collected leaves from fallen branches. To create a connection to the landscape, I have spun a large quantity of local fleece into yarn. I used this yarn as warp as well as weft. I dyed some of the yarn with the leaves of eucalyptus. This creates a golden colour that I have included in some of the pieces.

Lost 2020

woven tapestry

24 x 19 cm (framed)

Tangled 2020

water colour

32 x28 cm (framed)

Study for Miranda 2019

Water colour

25 x 18 cm

Miranda 2019

Woven tapestry

46 x 35 cm

Bracken Lace 2020

woven tapestry

27 x 33 cm

Fetching the Broom 2019

water colour

40 x 31 cm (framed)

Frond 2019

woven tapestry

23 x 19 cm (framed)

Joan’s Dream 2019

water colour

35 x 28 cm (framed)

The Return 2020

woven tapestry

28 x 19 cm

Heard Not the Voice of a Bird 2019-2020

woven tapestry

112 x 122 cm

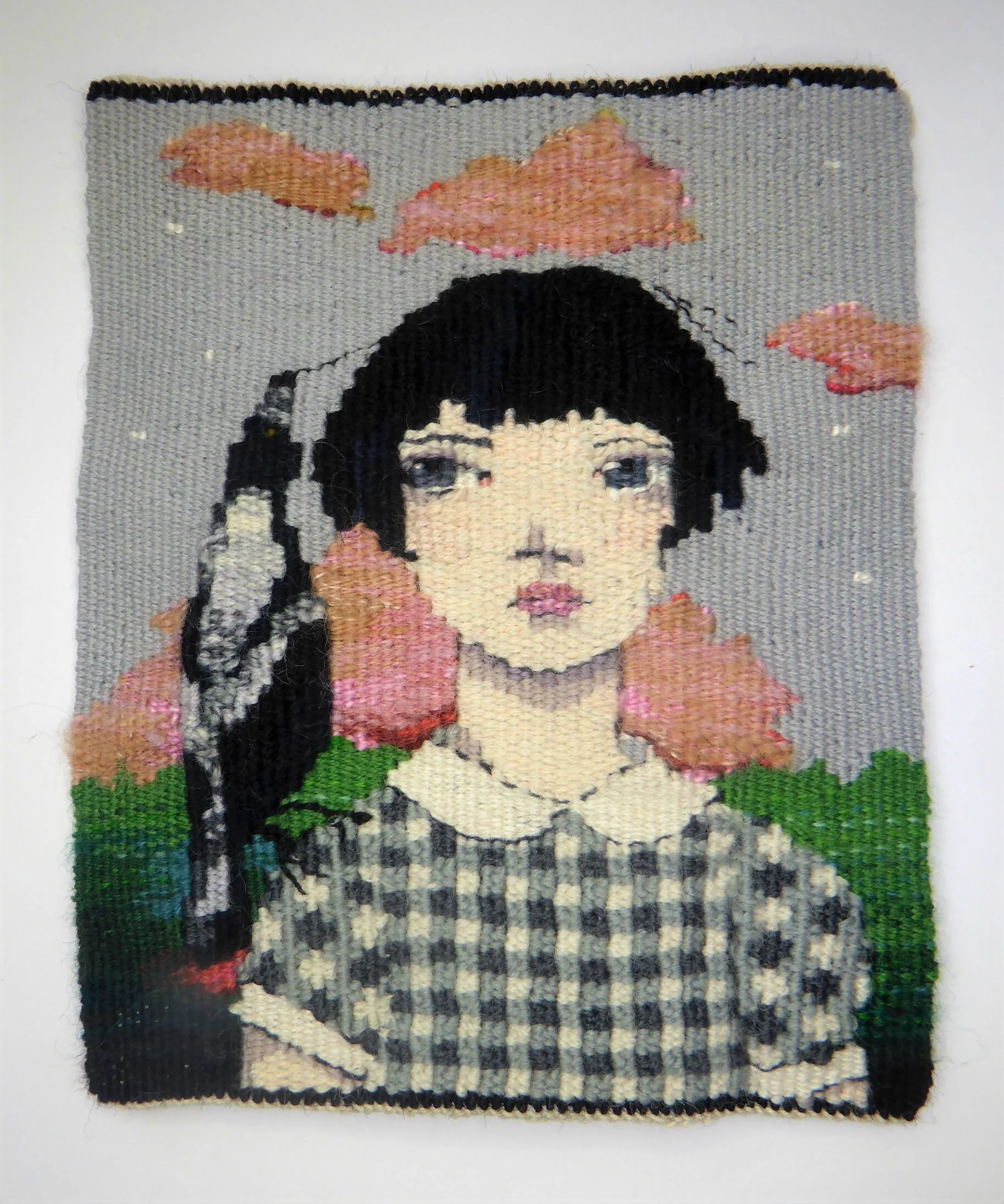

Girl and Magpie 2020

woven tapestry

14 x 12